Decades before ChatGPT, Tesla autopilot and Siri, there was Julian Feldman and a monstrous mainframe.

It was 1968, and UCI’s interdisciplinary program in information and communication science had just become a pioneering, standalone computer science department. At the helm was Feldman, who had co-edited a groundbreaking anthology of AI research a few years earlier. His fledgling department soon expanded UCI’s original computing courses – which had mentioned artificial intelligence concepts – to include graduate seminars and workshops devoted to the subject. But the lessons were largely theoretical.

“A lot of the ideas we’re using now were around then,” says Padhraic Smyth, Chancellor’s Professor of computer science. “But they couldn’t do them in the 1960s because computers were too primitive.”

Indeed, when Feldman’s book was reissued in 1995, co-editor Edward Feigenbaum wrote the preface on an Apple Macintosh that he said possessed “far more processing power, more RAM, and more disk memory than the sum of all the computers that were being used by all the AI researchers [from] 1956-62.”

Plus, the Mac was vastly smaller. The ICS building’s first computer system was so massive that cranes were required to lift the machinery to the second floor, where the windows had been removed to get everything inside, Feldman recalls.

From those humble beginnings, ICS faculty and alumni helped pioneer some of the computing world’s most important advances, including HTTP and the domain name system, two cornerstones of the internet.

In the 1980s, UCI began earning international recognition for machine learning, a branch of AI in which a computer teaches itself a task by analyzing images or data. The university is particularly famous in the AI universe for its Machine Learning Repository, a storehouse of datasets on such disparate topics as Pittsburgh bridges, Asian religious texts, perfume, diabetes, Bach chorales and balloons. Launched in 1987 by Ph.D. student David Aha, the repository is used by AI scientists around the globe to test algorithms.

Thanks in part to the advent of powerful video game computer chips in 2012, AI has caught fire in recent years – and spread to departments across campus.

Inspired by everything from rodents to Rubik’s Cubes, UCI researchers are developing the next generation of AI technology. Some are spearheading projects to improve healthcare or solve crimes. Others use AI to create interactive art or grapple with climate change.

The range is all over the map.

Cognitive sciences professor Jeff Krichmar, who once worked on anti-ballistic missiles for Raytheon, is trying to adapt animal brain processes to enhance AI navigation tools. Deanna Shemek, professor of European languages and studies, is directing a “digital necromancy” effort that would enable people to “converse” with a dead Renaissance princess, whose responses would come from the 30,000 letters she wrote during her lifetime.

Elsewhere on campus, the law school is leading programs to tackle the ethical and legal quandaries posed by AI. And the School of Social Sciences is cooking up discrimination-free algorithms for analyzing loan applications. The list goes on.

Even the library has gotten in on the act – with ANTswers, a chatbot that recommends books, searches catalogs, and responds to questions both serious and silly.

Q: How many toes do anteaters have?

A: I have four toes on each paw, with an additional vestigial fifth, but only 3 of my toes have prominent claws. It makes it hard to type.

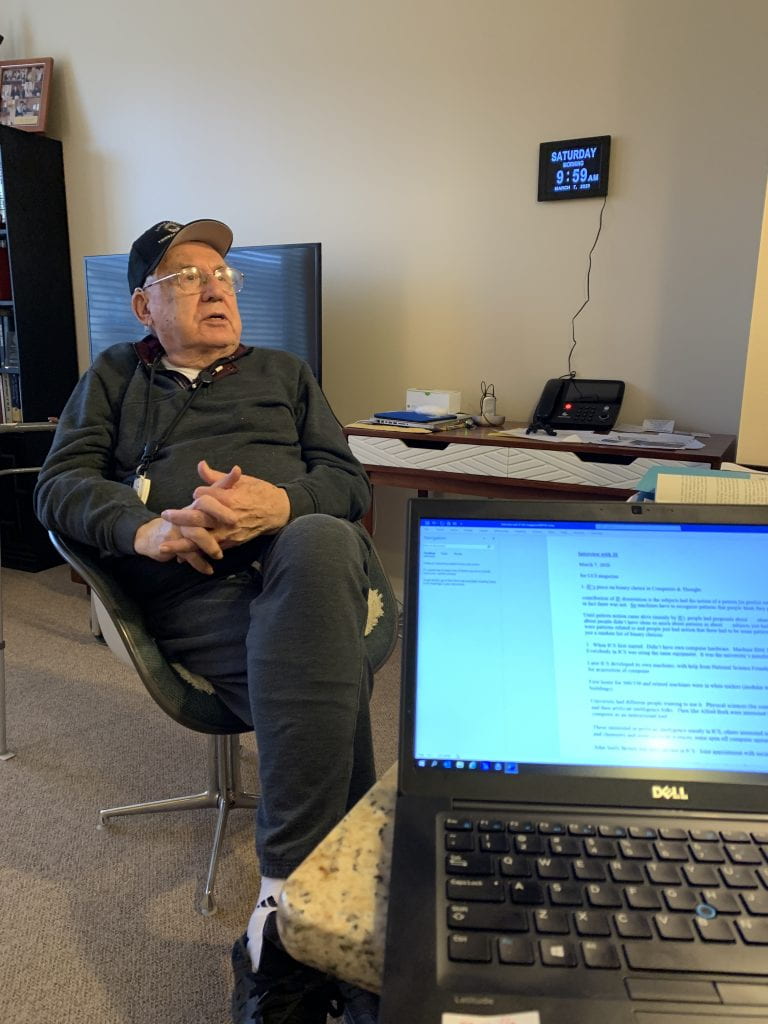

None of this was envisioned by Feldman. “In 1968, it was very hard to predict where things were going,” he says, because early AI research was so theoretical.

Today, it’s still tough to make forecasts, says ICS’s Smyth: “My colleagues and I are always wrong. But I can safely say there’ll be surprises.”